[ad_1]

The existence of black holes is no longer in question—we’ve detected plenty and even taken pictures of two of them. However, all the black holes we’ve found are either big enough to anchor a galaxy or about the size of a large star. In between is a no-man’s-land bereft of black holes. The search for “intermediate-mass black holes” is ongoing, and astronomers think they might have spotted one in our backyard.

Astronomers have long suspected that globular clusters are a good place to look for middleweight black holes. These super-dense spherical clusters of stars all formed around the same time and are usually older than surrounding objects. Previous studies of globular clusters have detected high mass toward the center that could suggest an intermediate-mass black hole, but the data has always been inconclusive.

A team of NASA and ESA scientists have used two powerful telescopes, Hubble and Gaia, to continue hunting mid-sized black holes. They’re focusing on the globular star cluster Messier 4 (above), which at 6,000 light-years away, is the closest object of its type to Earth. The problem is that we can’t see black holes unless they are actively swallowing nearby objects. That’s where the unique capabilities of these two observatories come into play.

There are at least 100,000 stars in Messier 4, but the Gaia team was able to map the gravitational constraints of the cluster by scanning 6,000 of them. Gaia is designed to determine the location and proper motion of stars with high accuracy, making it perfect for this task. Astronomers followed up on the Gaia observations with 12 years of Hubble data on stars in Messier 4, allowing the team to pinpoint a substantial mass. “We have good confidence that we have a very tiny region with a lot of concentrated mass. It’s about three times smaller than the densest dark mass that we had found before in other globular clusters,” said study lead Eduardo Vitral of the Space Telescope Science Institute.

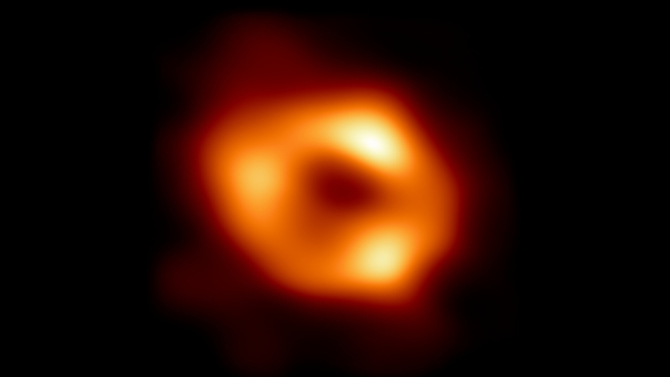

An image of our galaxy’s supermassive black hole (Sagittarius A*) as seen by the Event Horizon Telescope Collaboration.

Credit: EHT

This data showed there is indeed something massive inside Messier 4. Based on that, the team estimated the globular cluster is home to something with about 800 solar masses, which regularly affects the motion of surrounding stars. There’s no guarantee it’s an intermediate-mass black hole, but it’s in the correct range. The alternative explanation for this data doesn’t make much sense: 40 stellar mass black holes crammed into a space smaller than our solar system.

If this does turn out to be an intermediate-mass black hole, it could help explain why we see so few of them, and that, in turn, could clarify how supermassive black holes come to be. We know that stellar mass black holes form from the gravitational collapse of large stars, but do these objects simply eat and merge until they become supermassive? Studying the missing link in Messier 4 might provide an answer.

[ad_2]

Source link