[ad_1]

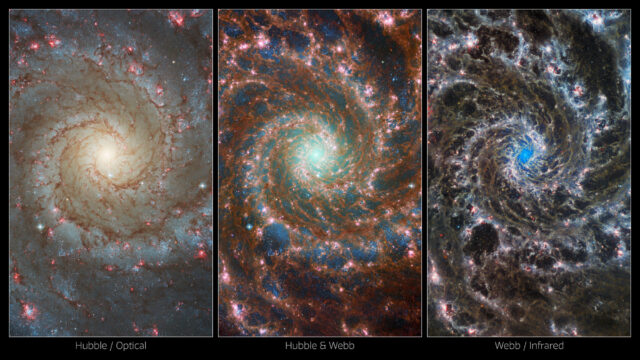

The James Webb Space Telescope is changing the way we see the universe. The instrument’s cutting-edge optics and ultra-sensitive infrared imager can see even more detail than the aging Hubble Space Telescope, and astronomers recently turned it toward an object known as M74, or more stylishly, the Phantom Galaxy. This spiral galaxy was one of Hubble’s most famous shots, and now we’re seeing it in a whole new light.

The Phantom Galaxy is about 32 million light-years away in the constellation Pisces. It’s one of a sub-type of spiral galaxies known as a “Grand Design Spiral” because the whirlpool-like arms extending from the core are bright and well-defined. It’s also directly facing Earth, which makes it a favorite target for astronomers.

Following its launch in late 2021 and subsequent commissioning in space, time on the James Webb Space Telescope has been in high demand. The PHANGS (Physics at High Angular resolution in Nearby GalaxieS) survey has used various observatories to study star formation, and now it has new observations of the Phantom Galaxy with the Webb Telescope. The team used Webb’s Mid-InfraRed Instrument (MIRI) instrument to peer right into the heart of this stunning spiral.

In the iconic Hubble images, the galaxy is studded with bright pink dots. These are actually enormous clouds of hydrogen gas, which are known as HII regions. They glow due to the ultraviolet radiation from newly forming, super-hot stars. Hubble operates in the visible and ultraviolet wavelengths, and now Webb adds the infrared, providing an almost ghostly structural element to the Phantom Galaxy.

New images of the Phantom Galaxy, M74, showcase the power of space observatories working together in multiple wavelengths.

The European Space Agency (ESA) notes that Webb is able to detect the delicate filaments of gas weaving through the spiral arms, which were not visible with Hubble. The relative lack of gas in the core of the galaxy allowed Webb to capture an unobscured image of a nuclear star cluster at the galaxy’s center. Above, you can see how Hubble and Webb data can be combined to provide a more complete image of M74.

The James Webb Space Telescope is so sensitive in the infrared that it could never operate correctly in low-Earth orbit like Hubble. That’s why it had to jet all the way out to the Earth-Sun L2 Lagrange point, more than a million miles away. There, it can remain nice and cool as it scans the universe to return amazing images like the new Phantom Galaxy snapshots. Webb still has about 20 years of operation ahead of it — this is only the beginning.

Now read:

[ad_2]

Source link