[ad_1]

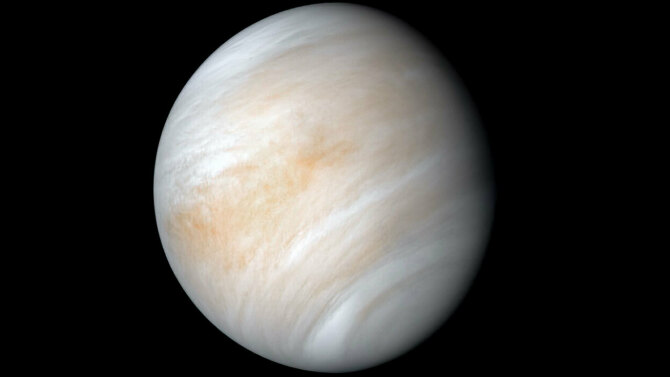

Venus may be Earth’s sister planet, but astronomers made that connection before knowing what this nearby world was really like. It has clouds of sulfuric acid and surface temperatures hot enough to melt lead, making it a profoundly alien environment. Venus also has thousands of active volcanoes, but the mechanism of the planet’s geological activity is still a mystery. A team from the Southwest Research Institute (SwRI) has a novel suggestion. They claim Venus owes its volcanism to cataclysmic asteroid or comet impacts.

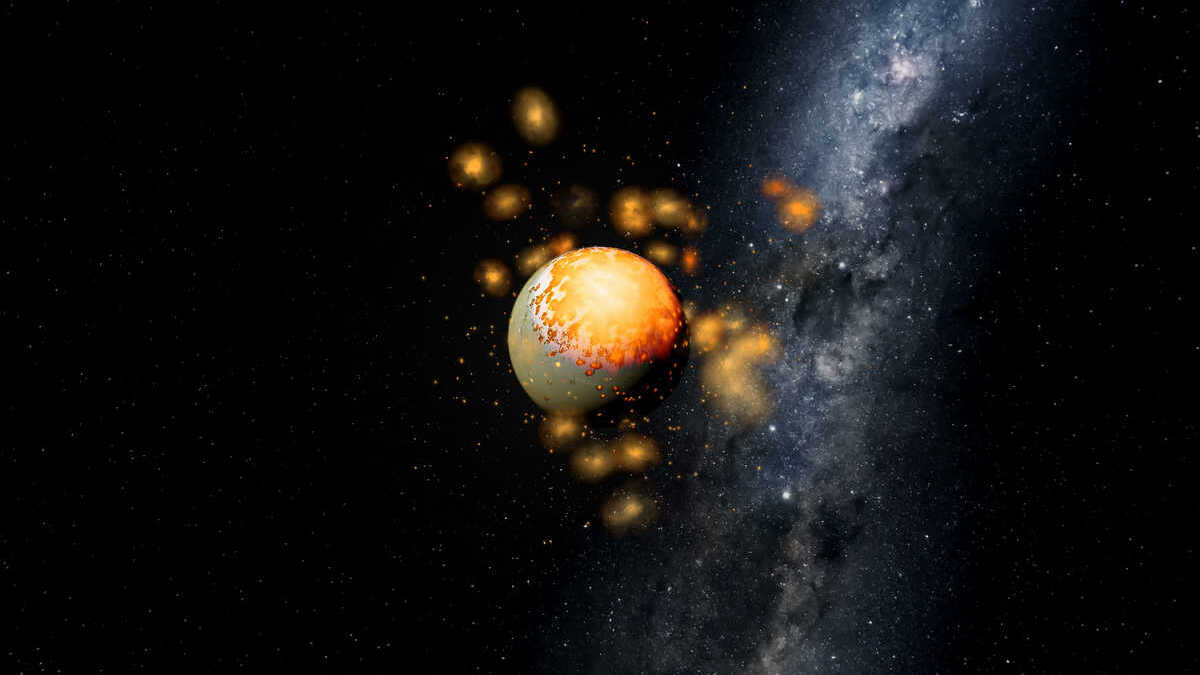

Venus is a difficult planet to study due largely to its ultra-dense atmosphere of carbon dioxide, which is almost 100 times more dense than Earth’s. Still, recent studies of Venus have shown evidence of active volcanism and bubbling magma. In one case, radar images showed surface changes from flowing lava, which helps to explain why Venus’ surface is only about a billion years old—it’s constantly being remodeled thanks to this geological activity. What we still don’t know is why. Venus has no tectonic plates like Earth does, so the SwRI team suggests that the heat driving this process may be left over from massive impact events in the planet’s past.

The SwRI team, led by Simone Marchi, notes that all the inner planets, Earth included, were pelted by material as the solar system formed, but Venus is slightly closer to the sun and orbits faster. That could “energize” impacts, causing long-lasting effects. The more powerful the collision, the more silica in the Venusian crust would melt. The team calculates that high-velocity impacts could have melted 82% of the planet’s crust. “This produces a mixed mantle of molten materials redistributed globally and a superheated core,” the group says.

Credit: NASA-JPL

It might have taken just a few large impacts to endow Venus with enough heat to fuel thousands of volcanoes even to this day. The team modeled the geodynamic processes in such a scenario, finding that large impacts could explain the planet’s continued geological activity, even billions of years later. This research has been published in Nature Astronomy.

We may soon have more data on Venus to verify or refute this hypothesis. With interest in Venus increasing, several missions are planned for the coming years. NASA-JPL is working on the DAVINCI (Deep Atmosphere Venus Investigation of Noble gases, Chemistry, and Imaging) mission, consisting of an orbiter and an atmospheric probe. VERITAS (Venus Emissivity, Radio Science, InSAR, Topography, and Spectroscopy) will map the surface in high resolution. Both these missions could launch at the end of this decade.

[ad_2]

Source link