[ad_1]

A team of astronomers has used some of the most powerful telescopes on (and orbiting) Earth to make a first-of-its-kind observation. They’ve spotted a pair of dwarf galaxies containing supermassive black holes on a collision course. Then, they did it again. Yes, two pairs of colliding dwarf galaxies, both extremely distant but at different phases of merging. Scientists hope this discovery can help shed light on how large galaxies like the Milky Way came to be.

A dwarf galaxy is one with less than 3 billion solar masses, about one-twentieth of the Milky Way’s mass. There are plenty of those drifting around in our corner of the universe, including several orbiting the Milky Way. None of them are about to collide, though. The current scientific consensus holds that the large galaxies common today arose from the merger of smaller ones, but ancient galactic mergers are difficult to observe because of their distance. The team, led by astrophysicist Marko Micic from the University of Alabama, got around that by combining data from the Chandra X-ray Observatory, infrared observations from NASA’s Wide Infrared Survey Explorer (WISE), and optical data from the Canada-France-Hawaii Telescope (CFHT).

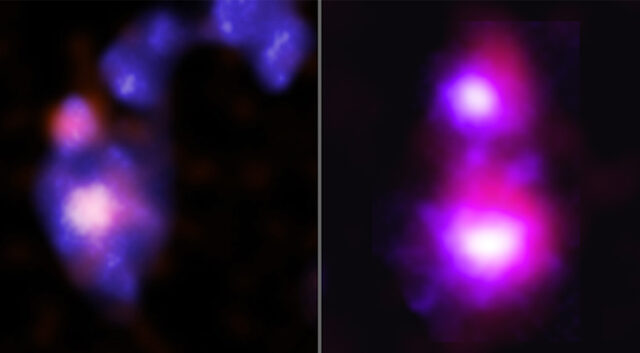

The orbiting Chandra observatory was particularly valuable in this study as it revealed the black holes, which are becoming more active as the galaxies move toward each other. The disk of super-heated material spiraling toward the event horizon heats up to millions of degrees, causing it to emit X-ray energy. This data pinpointed the colliding dwarf galaxies, and the visible and infrared data showed how the galaxies are interacting as they approach each other.

In the image above, the left composite shows a merger in galaxy cluster Abell 133, about 760 million light-years from Earth. Since the galaxies are in the late stages of merging, it’s been given a single name: Mirabilis, after an endangered species of hummingbird. On the right are the dwarf galaxies Elstir and Vinteuil, which are a reference to the Proust novel “In Search of Lost Time.” These galaxies are still separate, but a bridge of stars and gas has started to form between them. These objects are located in the Abell 1758S cluster some 3.2 billion light-years away.

With these objects identified, astronomers will be able to conduct follow-up observations that will reveal the processes taking place as they merge. In time, both pairs of galaxies will become larger dwarf galaxies with even bigger central black holes. This could cause more draw more small galaxies toward them, resulting in more mergers. Given the time scales involved, we can’t just stare at Elstir and Vinteuil until that happens, but astronomers have other sources of data. The James Webb Space Telescope recently revealed the Sparkler Galaxy, which appears to be a mirror image of a young Milky Way, studded with glowing globular clusters. This, too, could offer insight into how our galaxy evolved over the eons.

Now read:

[ad_2]

Source link