[ad_1]

Aurich Lawson | Getty Images

By now, you’ve probably heard about a new AI-based password cracker that can compromise your password in seconds by using artificial intelligence instead of more traditional methods. Some outlets have called it “terrifying,” “worrying,” “alarming,” and “savvy.” Other publications have fallen over themselves to report that the tool can crack any password with up to seven characters—even if it has symbols and numbers—in under six minutes.

As with so many things involving AI, the claims are served with a generous portion of smoke and mirrors. PassGAN, as the tool is dubbed, performs no better than more conventional cracking methods. In short, anything PassGAN can do, these more tried and true tools do as well or better. And like so many of the non-AI password checkers Ars has criticized in the past—e.g., here, here, and here—the researchers behind PassGAN draw password advice from their experiment that undermines real security.

Teaching a machine to crack

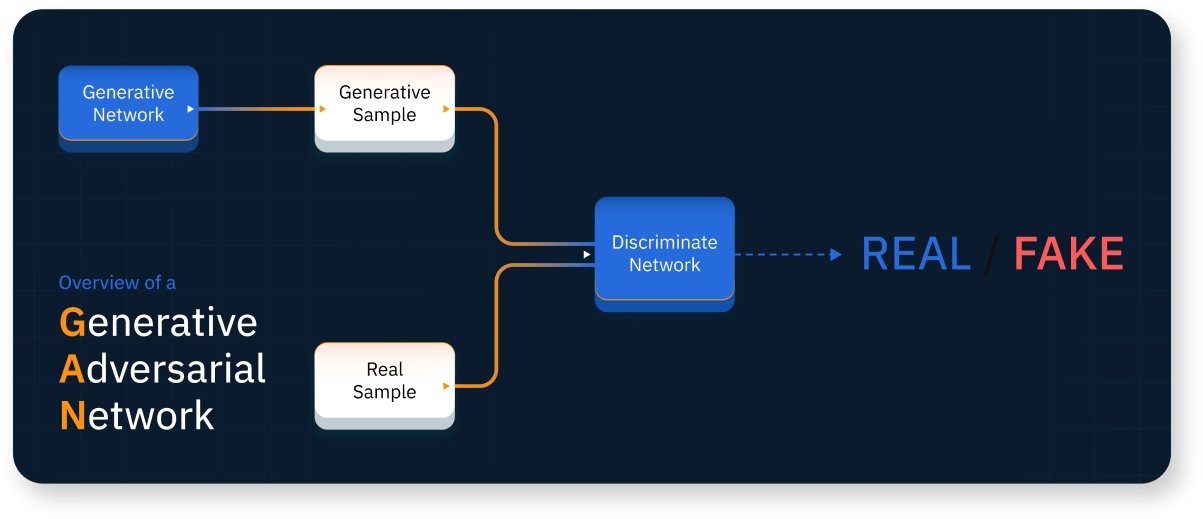

PassGAN is a shortened combination of the words “Password” and “generative adversarial networks.” PassGAN is an approach that debuted in 2017. It uses machine learning algorithms running on a neural network in place of conventional methods devised by humans. These GANs generate password guesses after autonomously learning the distribution of passwords by processing the spoils of previous real-world breaches. These guesses are used in offline attacks made possible when a database of password hashes leaks as a result of a security breach.

An overview of a generative adversarial network.

Conventional password guessing uses lists of words numbering in the billions taken from previous breaches. Popular password-cracking applications like Hashcat and John the Ripper then apply “mangling rules” to these lists to enable variations on the fly.

When a word such as “password” appears in a word list, for instance, the mangling rules transform it into variations like “Password” or “p@ssw0rd” even though they never appear directly in the word list. Examples of real-world passwords cracked using mangling include: “Coneyisland9/,” “momof3g8kids,” “Oscar+emmy2″ “k1araj0hns0n,” “Sh1a-labe0uf,” “Apr!l221973,” “Qbesancon321,” “DG091101%,” “@Yourmom69,” “ilovetofunot,” “windermere2313,” “tmdmmj17,” and “BandGeek2014.” While these passwords may appear to be sufficiently long and complex, mangling rules make them extremely easy to guess.

These rules and lists run on clusters that specialize in parallel computing, meaning they can perform repetitive tasks like cranking out large numbers of password guesses much faster than CPUs can. When poorly suited algorithms are used, these cracking rigs can transform a plaintext word such as “password” into a hash like “5baa61e4c9b93f3f0682250b6cf8331b7ee68fd8” billions of times each second.

Another technique that makes word lists much more powerful is known as a combinator attack. As its name suggests, this attack combines two or more words in the list. In a 2013 exercise, password-cracking expert Jens Steube was able to recover the password “momof3g8kids” because he already had “momof3g” and “8kids” in his lists.

Password cracking also relies on a technique called brute force, which, despite its misuse as a generic term for cracking, is distinctly different from cracks that use words from a list. Rather, brute force cracking tries every possible combination for a password of a given length. For a password up to six characters, it starts by guessing “a” and runs through every possible string until it reaches “//////.”

The number of possible combinations for passwords of six or fewer characters is small enough to complete in seconds for the kinds of weaker hashing algorithms the Home Security Heroes seem to envision in its PassGAN writeup.

[ad_2]

Source link