[ad_1]

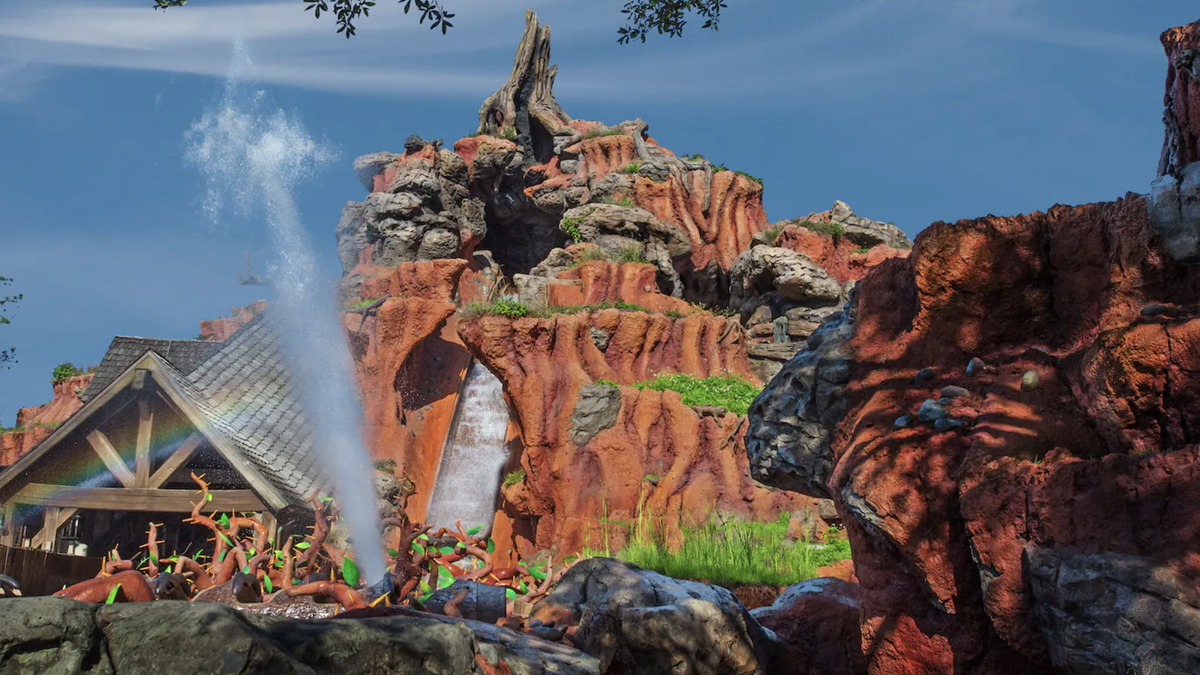

On closing day for Splash Mountain at Walt Disney World, wait times exceeded three hours. Fans of the Magic Kingdom’s 1989 water log attraction gathered to say goodbye; among them were folks genuinely looking forward to the Tiana’s Bayou Adventure re-theme. Then there were the disgruntled extremists who were still clinging to the ride as if it were one of their own Confederate monuments.

With those heightened emotions associated with the latter—something that isn’t much of a surprise, considering all the petitions filed against the ride’s Princess and the Frog redesign—comes a chance to cash in. And so water allegedly taken from the flume ride has made its way onto eBay, where jars are going anywhere from 20 to 50 bucks a pop. Truly, we’ve reached the lowest form of South of the South commodification in its long history of doing just that, from the Uncle Remus tales “written” by Joel Chandler Harris in 1880, to the 1946 Disney feature, to the late-1980s creation of Splash Mountain.

I’m not going to mince words here: certain fans’ normalization of Splash Mountain as its own entity has downplayed the role Song of the South has within the attraction, claiming it gets an exemption from the story’s overt racism because none of its human characters—i.e., the slave storyteller Uncle Remus and his master’s children—are featured on the ride, which instead included just the happy-go-lucky animal critters.

Harris might have created the “kindly-type” characters of Uncle Remus and his master’s family, but he appropriated the animal folklore from slaves, with critter characters like Br’er Rabbit originally serving as allegories for the plight of African Americans during slavery on the path to freedom. Disney Imagineers in the late 1980s were apparently unaware of this and assumed the animated rabbit and friends were fair game to use on Splash Mountain; Disney fans in turn presumed they were unrelated to the racist elements of the original story. In fact, Harris’ “of its era” misaligned re-telling of this folklore by a white man inspired another white man, Walt Disney, to commodify Black cultural resistance stories though an idyllic lens of the post-Civil War South.

G/O Media may get a commission

In 2012, African American literary great Alice Walker wrote in the Georgia Review that “Uncle Remus in the movie saw fit to ignore, basically, his own children and grandchildren in order to pass on our heritage—indeed, our birthright—to patronizing white children who seemed to regard him as a kind of talking teddy bear. I don’t know how old I was when I saw this film—probably eight or nine—but I experienced it as a vast alienation, not only from the likes of Uncle Remus—in whom I saw aspects of my father, my mother, in fact all Black people I knew who told these stories—but also from the stories themselves, which, passed into the context of white people’s creation, I perceived as meaningless. So there I was, at an early age, separated from my own folk culture by an invention.”

Now, Disney did get into it with the Harris estate as Song of the South was set to be released, as noted in the film’s notes on Turner Classic Movies—it wasn’t happy with his removing a reference to Uncle Remus from the film’s title, not disclosing his status on the plantation he worked on, and shifting the era of the film ever so slightly. Which sure, is something for a film released in the mid-‘40s, yet Disney kept the African American vernacular as a major plot point to the film; it’s embraced by a white child character against his father’s wishes. This brings a lot of new context to the story, and to the lyrics of Song of the South tunes like “Zip-a-Dee-Doo-Dah”—which was heavily featured as a staple of Splash Mountain—making lots of Disney World visitors over the years unwitting participants in the easily digestible commodification of Black culture that the movie presented.

Disney carries blame here for pretending the film can just be tucked away, aside from the parts that made it money for as long as they did, and hoping audiences wouldn’t notice. Select films on Disney+ have begun to feature warning labels, holding certain releases accountable when they contain problematic, outdated material—but Song of the South’s fate is a little more complicated. Back when the streamer became available, Deadline shared Disney CEO Bob Iger’s response to an audience question regarding the film’s absence from Disney+ , and he firmly asserted that the film is “not appropriate in today’s world,” which it’s not. Distressing, however, is the conjecture of assuring audiences it was a product of its time—despite TCM’s chronicle making note of protests upon the film’s release, including picket lines that were racially integrated efforts from the National Negro Congress, the American Youth for Democracy, the United Negro & Allied Veterans, and the American Jewish Council at cinemas in major U.S. cities. At the time the NAACP objected to the film, saying that “in an effort neither to offend audiences in the North or South, the production helps to perpetuate a dangerously glorified picture of slavery… [the film] unfortunately gives the impression of an idyllic master-slave relationship which is a distortion of the facts.”

Disney’s stance of “let’s just throw it all away” was not an ideal strategy for addressing the issues that still surround Song of the South—evidenced by the large number of Disney fans who have professed nostalgic loyalty to Splash Mountain. That some showed up in droves to make a quick buck off cups of log flume water affirmed the existence of bigoted fans who felt like a part of their history was being stolen, inspiring them to circulate petitions against diverse employees at Disney Imagineering and its attempts to create inclusive stories. It’s all encapsulated by the hate they hold as represented by the water in jars; they can just look at instead of letting themselves be hit with the cold splash of reality.

Disneyland’s Splash Mountain has yet to announce a closure date. Tiana’s Bayou Adventure is set to open in 2024.

Want more io9 news? Check out when to expect the latest Marvel, Star Wars, and Star Trek releases, what’s next for the DC Universe on film and TV, and everything you need to know about the future of Doctor Who.

[ad_2]

Source link